BOSTON BULL'S-EYE CAMERA

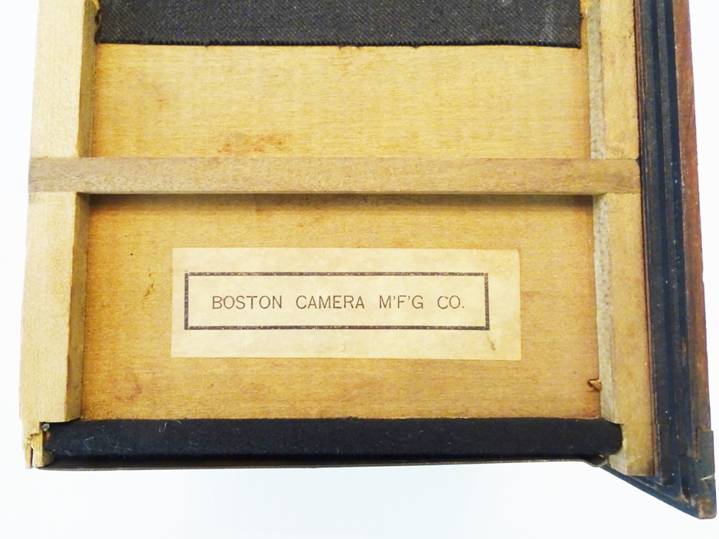

Boston Camera Manufacturing Company,

Boston, Massachusetts 1892 -

1895

Capable of 12 exposures on 3-1/2 x 3-1/2 roll film, and the first to

carry the name, the Bull's-Eye Camera

was introduced by the Boston Camera

Manufacturing Company in 1892.

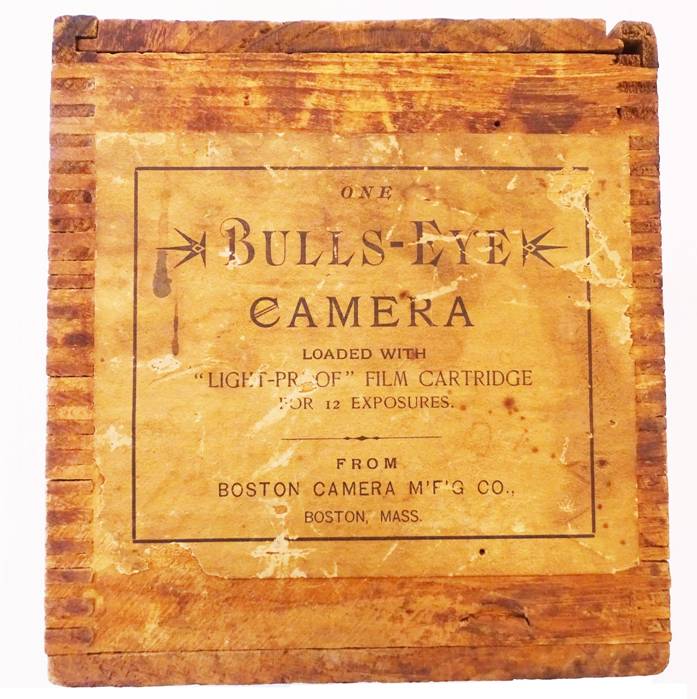

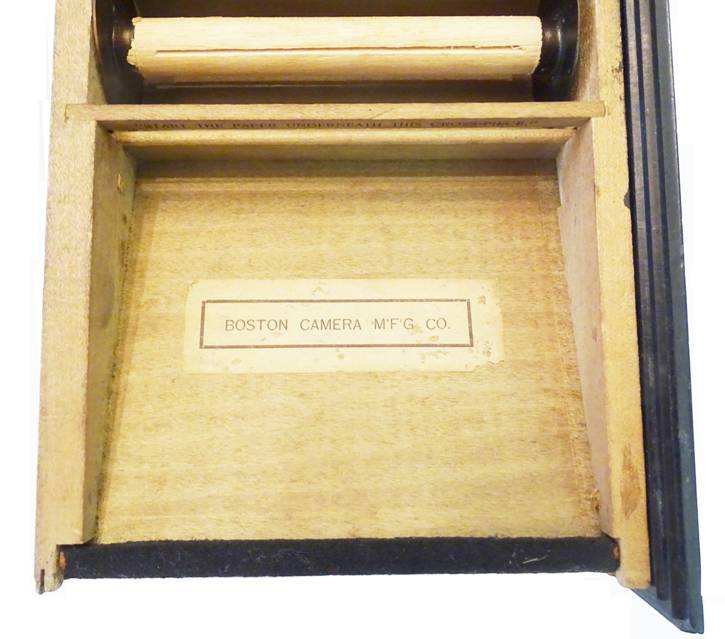

Boston Camera Mfg.'s ads spelled the name as "Bull's-Eye" with an apostrophe, yet it's not reflected

in their box labeling as seen above. Eastman Kodak would later spell it without

the apostrophe. It's unique D-shaped red celluloid window indicated the roll

film's exposure number. The window is of significance to collectors for two

reasons.

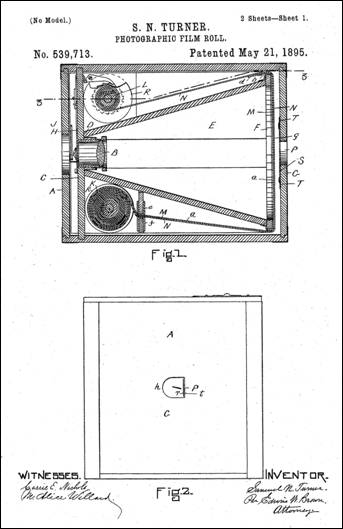

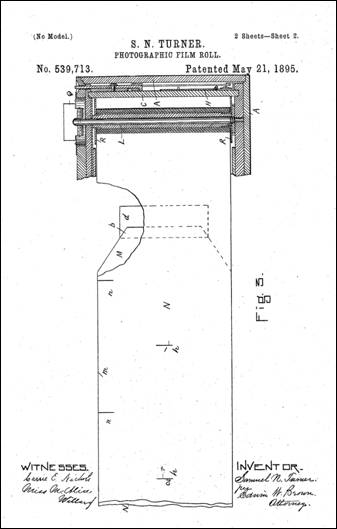

First,

this window feature was part of a daylight-loading film system, designed by

Samuel N. Turner, Boston Camera Manufacturing's founder, under Patent No. 539,713 granted May

21,1895. George Eastman saw the

potential in this daylight-loading system, and after failing in his attempts to

purchase the patent, he would end up acquiring the entire Boston company in

August, 1895. Eastman would

continue production of the Bull's-Eye

Camera, renaming it the No. 2 Bulls-Eye

and equipping it with a round film window.

The rest is history with virtually every Kodak roll film camera

thereafter incorporating this feature.

Source: Google Patents

Secondly,

the D-shaped window which is shown on the patent drawing, has always been a

mystery to most collectors. Reviewing

the patent's wording, the reason for its shape becomes evident. The exposure numbers on the film's backing

were underlined, and as one wound the film they would position that line as

close as possible to the flat side of the D.

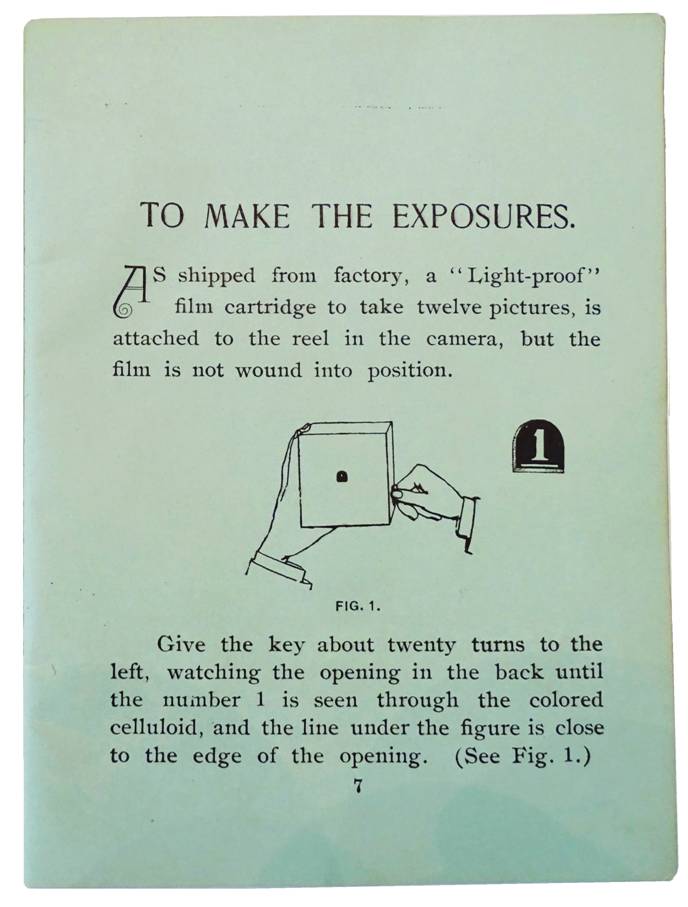

This is supported by the illustration below, in Boston Camera

Manufacturing's Instruction Book

for the Bull's-Eye copyrighted May, 1892.

It depicts the user rotating the camera 90 degrees, and grasping the

winding knob to advance the film in preparation for the next exposure. The

illustration further shows the number and underlining, as it would appear

through the window. Another benefit of this arrangement not outlined in the

patent, is that the flat side of the D served to confirm the exposure

number. With the number underlined,

there would be no mistaking a "6" for a "9". This was important to know when you only had

12 exposures. All this becomes more

logical, supported by the D's flat side position in relation to the direction

of the film travel while being wound. It

further makes sense that the photographer would naturally rotate the camera 90

degrees off vertical to make winding easier (assuming one is right-handed), and

at the same time being able to easily and correctly read the number in this

position.

Boston

Camera Manufacturing's Instruction

Book for the Bull's-Eye copyrighted May, 1892

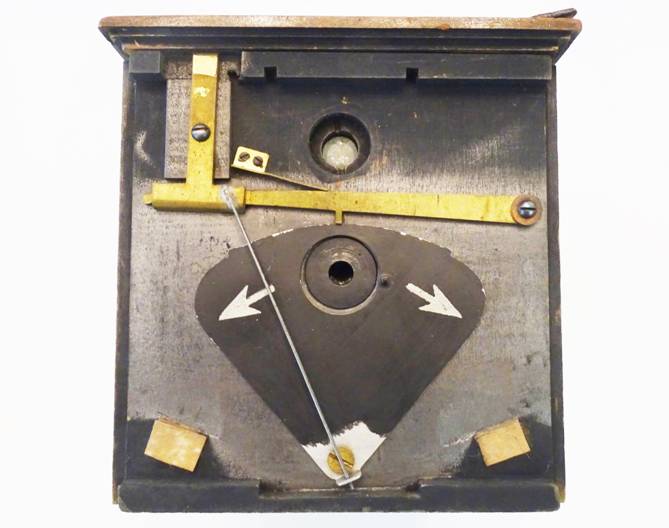

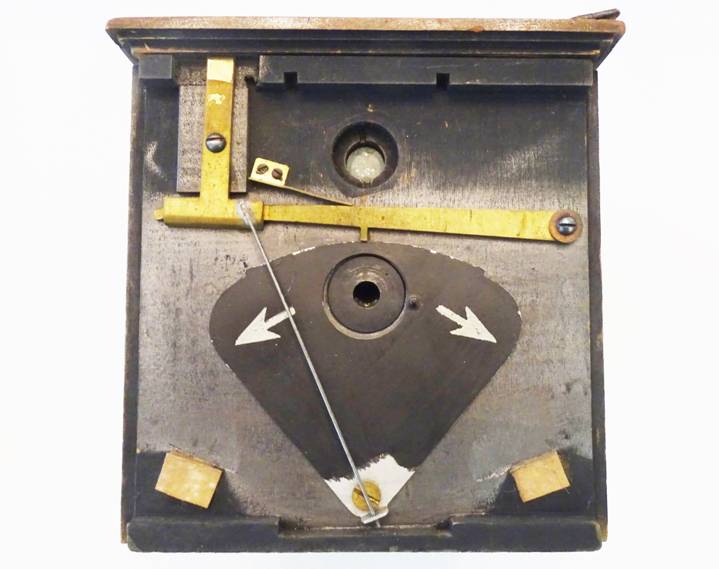

The origin of the Bull's-Eye's shutter design came from Abner G. Tisdell

(of Tisdell & Whittelsey

Detective Camera fame) under Patent No.

464,260 dated December 1, 1891. Tisdell was

granted at least four photographic patents during the late 1880's and

mid-1890's:

Source: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office Boston Bull's-Eye Shutter

Per Jos Erdkamp's

great article on this camera, The

Legacy of the Boston Bull's-Eye Camera,

"The shutter was designed by Frederick H. Kelley at Blair Camera Company

in 1892, and it was a modification of Abner G. Tisdell's shutter (United States Patent 464,260)".

Fred H. Kelley, as a co-patentee, held at least five

other patents with Thomas H. Blair, two of which were shutter designs for the Blair Hawk-Eye Detective and the Blair Kamaret.

Comparing Tisdell's patent drawing alongside the

Bulls-Eye's shutter, the similarities are evident. It's undetermined whether

Kelley ever applied for or secured a patent for his modified design.

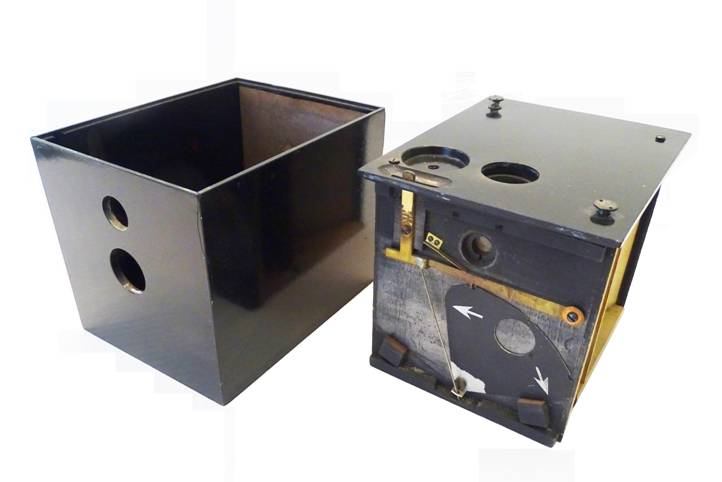

Boston's

Bull's-Eye was offered in at least

three known versions: leather-covered

wood, natural wood and Ebonite, a thermoplastic material. None of them are common today, but the

leather-covered version is the one most often encountered. Both the wood and

ebonite versions are much rarer, and not many of either have survived. I would give the ebonite version an edge in

rarity, probably being the most difficult to find, especially in very good

condition. Despite the material's

hardness, ebonite is considerably more fragile than wood, easily cracked or

damaged if dropped and prone to warping at extreme temperatures.

For information on Boston

Camera Manufacturing Company's other Bull's-Eye models, look for them under the "Antique Cameras" section of this website.

For more information on Boston's Bull's-Eye Cameras, as well as Eastman

Kodak's earliest models, follow this link to Jos Erdkamp's wonderful site "Antique Kodak cameras from the

collection of Kodaksefke":

http://www.kodaksefke.nl/index.html

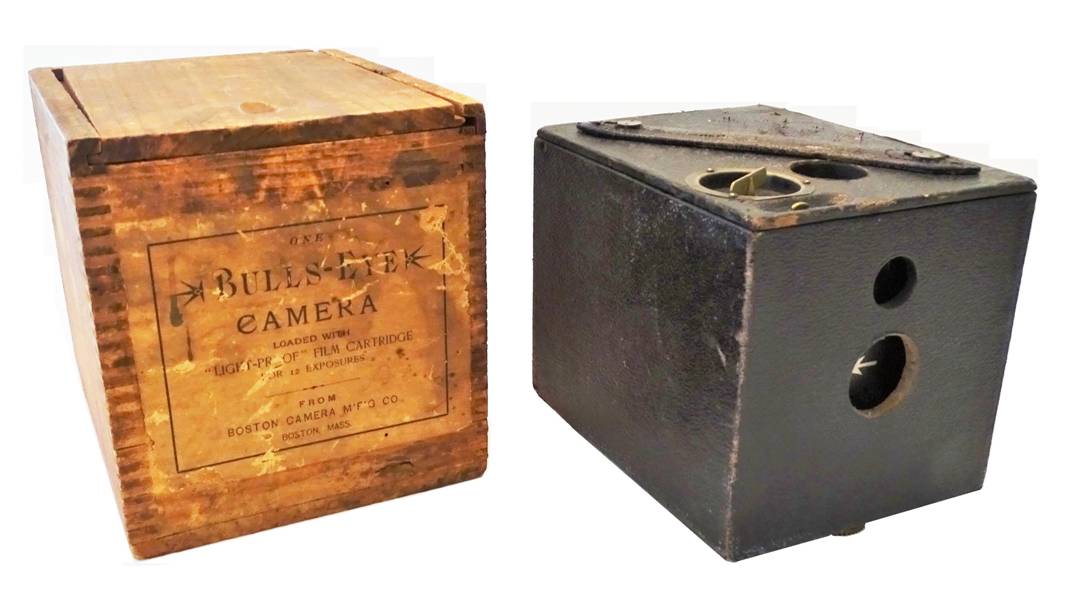

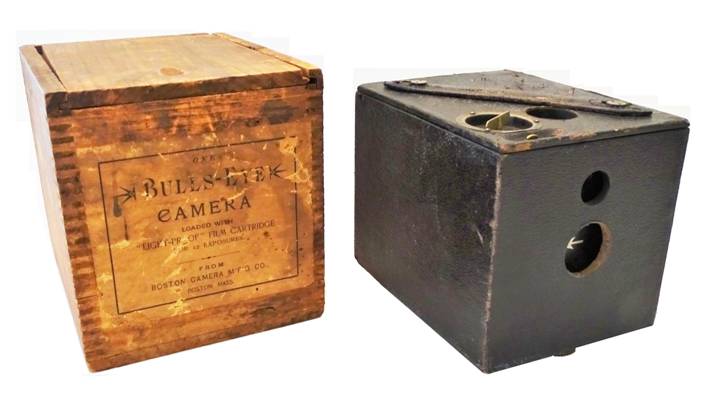

Leather Version

Leather-covered version with factory box

Wood Version

Ebonite Version

Boston

Bull's-Eye (left) shown alongside its successor, the Kodak No. 2 Bulls-Eye